Background

In this note, we present the findings from our analysis of 259 Polish software startups that did a seed or a series A venture capital round in the 15 years between 2006 and 2020.

Our analysis shows that an increase in VC capital has created more (near) unicorns without necessarily making it easier for a software startup to find its first institutional VC investor and to raise more in follow-on rounds. Early-stage VCs hedge their options by getting in early and doubling down on winners. Once a startup has raised VC capital, there is pressure to raise more in follow-on rounds. Only a relatively small number of startups manage to do that. Software tech entrepreneurs cannot hedge and have to focus on delivering flawless execution all the way through. Successful VC companies attaining unicorn status tend to raise capital in follow-on rounds every 18–24 months.

A rising tide of VC capital makes some proverbial startup boats rise faster than others

There is a clear and robust upward growth trend in the number of active VC funds, VC rounds, their size in dollar terms, and the total amount of dollars invested into Polish software startups between 2006 and 2020.

This is similar to the upward trend experienced across Europe and the global VC industry. There is an increasing amount of risk capital available distributed across more VC funds and regions. That’s good news for Eastern European economies like Poland, which lagged behind more mature VC markets.

However, this only sometimes makes it easier for a software startup to find its first institutional VC investor. A simple reason is that there is more competition, given the substantial growth in hopeful tech entrepreneurs pursuing the unicorn dream.

Moreover, in mature VC markets, there are signs of an increasing number of early-stage seed investments not followed up proportionally with investments at the next levels (especially series A). This makes it more difficult to raise an early-stage follow-on round.

Another trend that narrows startup funding options is the increase in round sizes necessary for VC funds to deploy all their capital raised. This, in turn, pushes up valuations as competition increases.

If you hear the following phrase, ‘the new seed round is the old series A round,’ it entirely refers to an increase in round sizes. For clarification, larger round sizes lead to higher valuations at standard dilution levels per round.

What’s clear from our Polish sample is that the startups that attract VC funding and manage to raise follow-on rounds end up taking an oversized proportion of VC capital. That’s especially true with a few startups with stellar traction where valuations and round sizes continue to increase. In this sense, a rising tide of VC capital makes some proverbial startup boats rise faster than others.

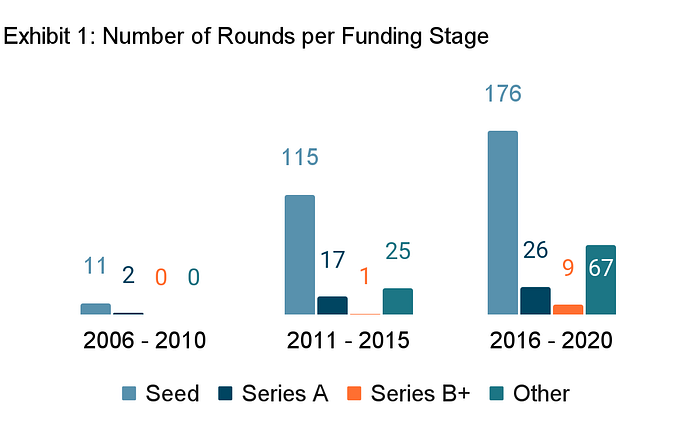

In the 15 years, our sample is based on 302 seed rounds and 45 series A rounds. This is based on how the round was disclosed and not on our definition of what a seed or a series A round size ought to be. There were an additional 102 rounds, such as funding & venture rounds (28), grants (24), series B/C/D/E rounds (10), non-equity assistance or accelerators (6), debt rounds (3), and other types (31).

Funding & venture rounds ranged from $25K to $7M; for example, one startup, Synerise, announced $17.8M in four separate venture rounds every consecutive year since 2017. Other such rounds not labeled as a particular series may be small bridge rounds or down rounds, where the valuation was lower than the prior round.

Exhibit 1 shows a significant growth in funding rounds across all stages. The increase during the three time periods is also very substantial. From 13 rounds in 2006–2010 to 158 rounds in 2011–2015, and 278 rounds in 2016–2020. Notice that not all of these rounds disclosed the actual amount raised.

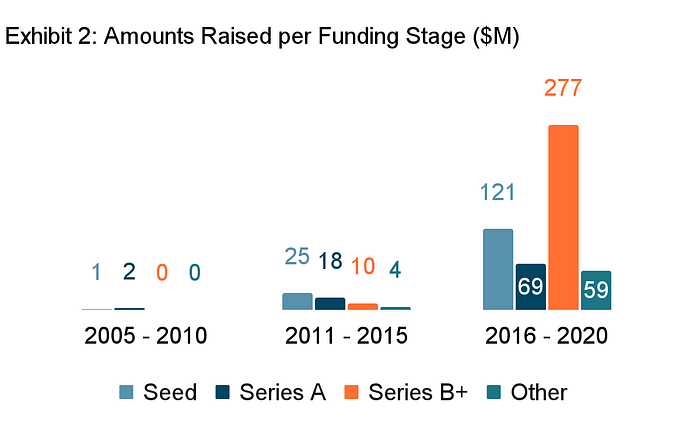

During the 15 years, a total fundraising amount of $585M was disclosed by the 259 startups in our sample. Of which just two startups, Brainly and DocPlanner, accounted for $296M. By the funding stage, seed rounds raised $146M, series A rounds raised $89M, higher series rounds (B/C/D/E) raised $287M, and other types of funding rounds accounted for the remaining $63M.

Exhibit 2 shows a significant increase in the amount invested over the 15 years, especially in series B and higher. The increase in total funding during the three periods is even more significant, going from $3M in 2006–2010 to $56M in 2011–2015 and $525M in 2016–2020.

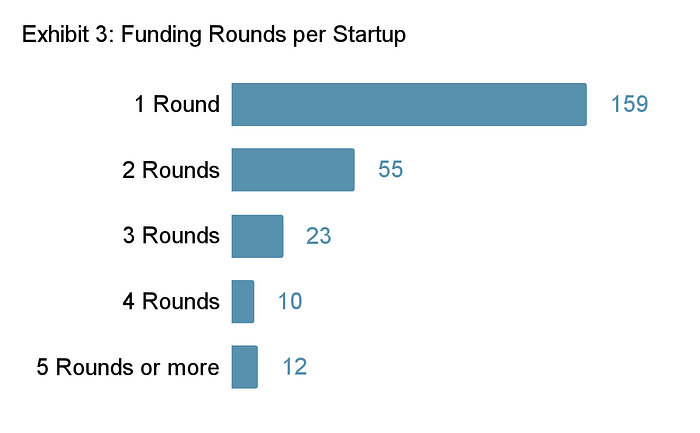

Exhibit 3 shows that of the 259 startups, 159 had by the end of 2020 only raised money in one type of round, whereas 55 raised two types of rounds, and the remaining 45 startups raised funds in three or more different types of rounds. Over 15 years, we expect a small proportion of startups that raised their first round before 2016 to have raised 2 to 4 follow-on rounds by now.

Every new equity round should ideally be at a higher valuation to limit the dilution to the founders. This is only sometimes the case. Some startups manage to raise small amounts in many pre-series A rounds. In our sample, 6 startups that raised money in 5 or more rounds did not raise more than $2M each.

The startups that have raised money for the first time in 2016 or after should have raised another round by now. If not, attracting a new VC investor will be difficult as it will worry about the following follow-on round.

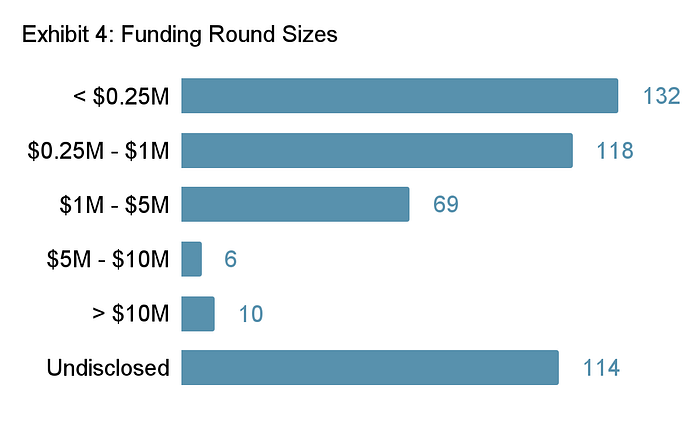

Exhibit 4 shows that out of 335 rounds with a disclosed dollar amount, a majority are below $1M. 10 startups raised between them 16 rounds of over $5M. 2 of which were seed rounds (Talent Alpha in 2019 and Nomagic in 2020). 4 of which were series A (Brainly, PerfectGym, Packhelp, and Infermedica), 8 series B+ (only Brainly and DocPlanner, where one C round amount for DocPlanner is not disclosed), 1 debt round (PayPo), and 1 venture round (Synerise).

VCs diversify, whereas tech entrepreneurs specialize

An early-stage VC raises separate funds over time. Each fund generally focuses on one or two funding stages (e.g., pre-seed and seed or seed and series A). Within this stage focus, the VC divides each fund into many, typically 15–25 startup investments. The earlier the stage focus, the higher the number of investments per fund. In addition to being stage-specific, most VC funds are geographic and industry vertical-specific. Nevertheless, VCs attempt to diversify themselves through exposure to non-competing startups in different sub-segments.

This diversification is done to index the fund portfolio to startups’ survival and success rate. Because, on average, one, at best two, of a fully invested fund portfolio of startups are likely to yield a glorious payback. Meanwhile, most portfolio startups will go out of business, end up as zombies, and, in a few cases, be sold for a decent cash-on-cash return. One thing is for sure, for every success that an early-stage VC can point to in a fully invested fund portfolio, there are at least three other startup investments that are doing so-so.

For every startup that fails to return the amount invested, another startup, assuming equal amounts invested in the two startups, has to produce a return of 8x. This is because it’s costly for a VC to raise money for investments in risky startups. VCs typically promise to return at least 3x their investor’s original money. This means that a VC must make an average of 4x after its fees on the money invested. Assuming 2 startups each receive $1M for a combined investment of $2M from the same fund. If one fails, the other has to make a return of $8M to make up the average of 4x cash-on-cash return. On average, a fund returning 3x to its investors will experience that one-third of its investments return nothing, one-third around one time, and the last one-third will return on average 10x.

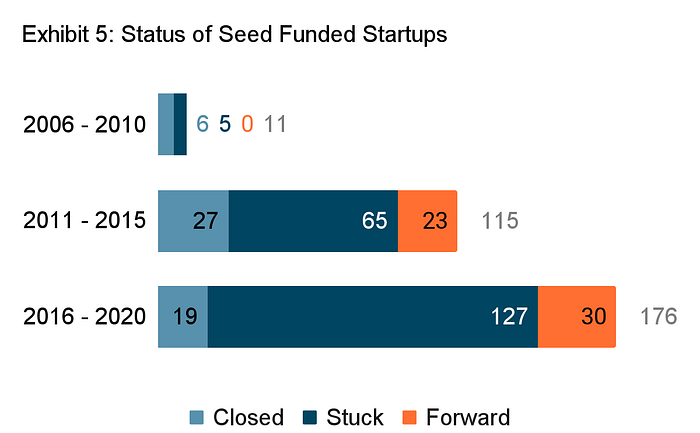

Exhibit 5 shows that of the 302 seed investments in our sample, we estimate that at least 52 have gone out of business, whereas 53 have raised more money in follow-on rounds. Of the remaining 197 “stuck” startups, 70 raised a seed round before 2016 and have not disclosed raising any new money before we closed our review.

These “stuck” startups are likely to have been put up for sale by their institutional VC investors. Important to note that a VC investor, even as a minority shareholder, can force a sale of the startup to a new majority shareholder because of its preferred drag-along shareholder clause. Early-stage VCs are likely to insist that the drag-along clause is in some form mandatory before investing. A tech entrepreneur needs to pay close attention to the exact wording of this clause, as it can dramatically alter the timing and valuation of an M&A exit.

The remaining 127 startups that we labeled “stuck” since 2016 are split into some startups that raised a seed round in 2016–2018 but may now struggle to raise a new round. Furthermore, it’s time for those startups that raised a seed round after 2018 to interact with series A investors gainfully.

That many startups fail or stall is not a surprise. A more relevant question in this context is why so many VC-backed startups are seemingly not making it, especially because startups that attract VC investments are already a curated group of promising startups. Actually, what difference can a VC with a minority stake make to the success rate of a startup?

Put differently: what else can a VC contribute to early-stage startups besides growth capital? To start with, the (lead) VC will demand a board position allowing the VC-designated board member to pass on the experience to the tech entrepreneur and the startup team. In addition, a VC can arrange and sponsor various activities, such as go-to-market approaches and networking events. Very importantly, the VC can help its portfolio startups to raise their next round of funding through the VC’s network and knowledge of what investors are looking for. In addition, the VC firm will have valuable insights into how the market currently values different types of startups.

The status of a VC can also signal to the market that the startup is an outstanding opportunity. Other than that, the tech entrepreneur and the team have to create, through hard work and some luck, the traction needed to scale up the startup.

This illustrates the difference between VC diversification to hedge risk and the intense focus and specialization required from a tech entrepreneur to succeed with a software startup.

The relative risk of a startup failure declines, and the time to monetize for a later-stage investor shortens with an increase in the size of a startup. This means late-stage investors (from series B rounds upwards) take on less economic return risk than early-stage investors. That’s another reason early-stage investors diversify their portfolio in rounds at low valuations, with the opportunity to follow on through pro-rata investment rights in later rounds.

Follow-on VC rounds are what matters

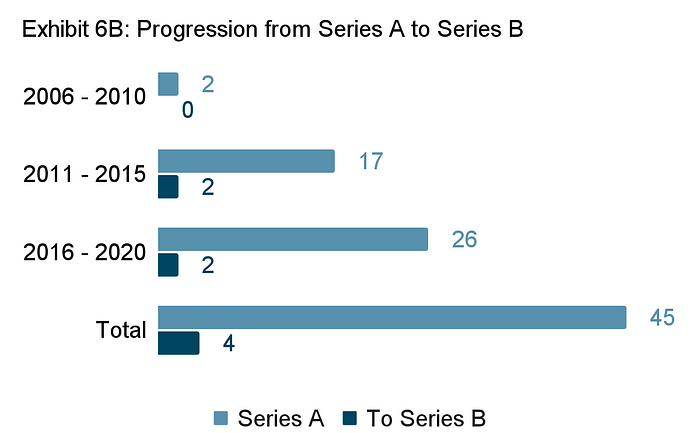

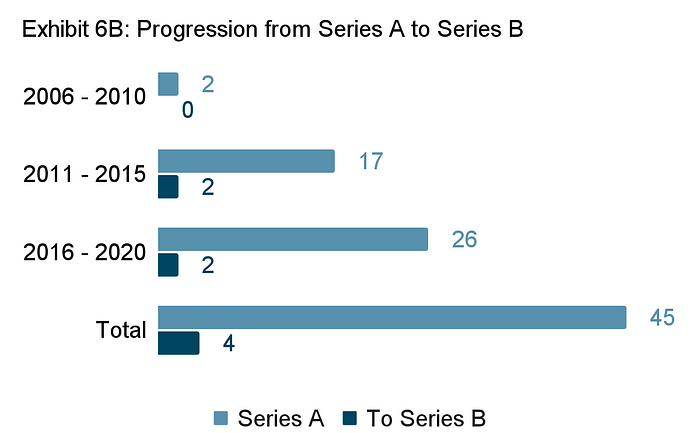

What we see from our relatively small Polish sample concerning follow-on rounds is behind the global VC trends. Exhibit 6A shows that approximately 10% of seed startups progress to series A (31 out of 302), and of that, as Exhibit 6B shows, 10% progress to series B (4 out of 45).

Put differently, out of 100 seed investments 10 follow-ons with a series A round and 1 follow-on with a series B round. This is below average compared to more mature markets where progression from seed to Series A is up to one-third.

For clarification, we considered if the cohort of seed and series A round startups during a five-year period went on, respectively, to raise a follow-on series A and series B round in the same or future five-year periods. For example, of the 115 startups that raised a seed round between 2011 and 2015, 10 did a follow-on series A round between 2011 and 2020.

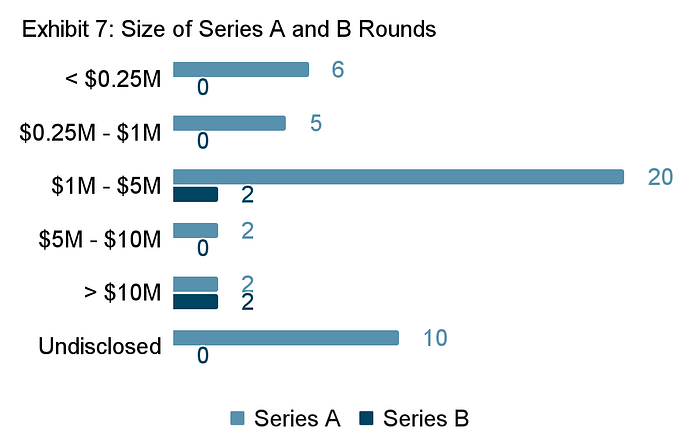

Exhibit 7 compares the round sizes of all the series A and B rounds in our sample. Of the 35 series A rounds with a disclosed amount, 11 were ‘very small’ rounds below $1M, and 20 were in a ‘small’ range of $1M to $5M, considering country and period. The remaining 4 series A rounds were relatively ‘normal’ at over $5M. Where 2 were above $10M. This is Packhelp which has done 3 financing rounds starting in 2017, and Infermedica which has raised money in a total of 7 rounds since 2012.

When we look into the details of the series B rounds, we see that 2 of the 4 rounds were relatively small at $0.9M and $3M, led by the same VC firm: IC Sec, that raised $7.3M in 4 rounds (not including a new round in 2021) starting with a seed round in 2016, and Senterit that raised $4.3m in 2 rounds starting with a series A round in 2017. Brainly and DocPlanner did the other two series B rounds at $29M (in two tranches) and $10M, respectively.

Receiving an early-stage VC investment is not a guarantee to find a follow-on investor, as Exhibit 5 shows. Attracting a new investor is difficult, and when successful is a job well done for a tech entrepreneur.

Early-stage software investors look to invest in best-in-class growth startups (sometimes known as ‘T2D3’ growth or 2x triple and 3x double revenue growth). This kind of annual hypergrowth requires a lot of capital which is what VCs have.

A startup founder may entertain the idea of bootstrapping growth after one or two grueling fundraising rounds. However, the risk to a VC is that a slower growth traction will make the size and timing of their potential exit of this investment unsatisfactory.

Generally speaking, early-stage institutional VC investors will be apprehensive about investing in an entrepreneur who is not ready to dilute ownership further to raise additional funding rounds. That’s another reason why the follow-on round is what matters.

The startup and the prior round investors usually benefit enormously from a follow-on round. A tech entrepreneur should remember this when a prospective seed stage investor calls the pro-rata investment right non-negotiable. It’s a great option for the VC and should not be given away lightly. For one, the seed investor can mark up their investment after a follow-on round and use it to raise a new fund.

Moreover, a tech entrepreneur might not appreciate at the beginning of a VC-funded journey that due to the pro-rata investment rights, a seed investor can remain the largest preferred shareholder through series A and up (if the VC fund or firm can make follow-on investments).

Take a simple and typical example: A seed investor previously bought 20% of new primary preference shares, leaving the founder with 80% of ordinary shares in the captable. In the series A round, the dilution is also 20%. The seed investor will then invoke its pro-rata investment right and buy enough new shares to maintain its preferred equity stake in the captable, thereby staying at 20%, the founder at 64%, and the new series A investor at 16%.

VC-funded startups are under pressure to fundraise repeatedly

Once a software startup raises its first early-stage VC seed capital, it’s expected to raise more rounds of VC capital. We’re not stating this to discourage anyone. On the contrary, it’s important that entrepreneurs understand the expectation in advance. The reason for this anticipation is that a few early-stage investments pay back an entire VC fund due to the low survival rate of startups.

Doing well in the early stage VC space means an investment returns the VC investor’s money 10x if not 100x when selling out to a great peer company or after an IPO listing. Considering dilution, this means turning an investment of $1M into a $10M to $100M cash out for a total company valuation of $100M to $1B. Imagine how much money a startup needs to raise in follow-on rounds to generate that value appreciation.

Moreover, the time it takes to return this money is also very important. Institutional investors, aka General Partners in a VC fund, have received money from their investors, aka Limited Partners, which can be former entrepreneurs, pension funds, and governments, that the GPs need to return to the LPs after a fixed period of 10–12 years. The pressure to continue fundraising for a startup that starts on this journey in follow-on rounds relates greatly to the time frame of delivering stellar returns.

The question is then: how much should a startup raise, and how often should it raise VC money? One benchmark is to raise enough money to make a difference in 18 months. A startup does not want to raise too much money at a too low valuation as it dilutes the owners’ stakes too much. As a software startup grows and proves itself, it will attract a higher valuation, resulting in less dilution for the same amount of capital raised. A fast-growing software startup ideally needs to raise money every 18–24 months with the ability to stretch the cash position to 30 months if the market conditions turn sour.

As VC transactions are private, we don’t know the actual performance of startups that raise subsequent rounds versus startups that fail to do so. Traction in spending and growth are key indicators a VC would consider before allocating capital to new investments.

All of this is nicely illustrated by the two startups in our sample, which raised a total of $296M, Brainly and DocPlanner. Since 2012 they have done a total of thirteen equity rounds. And, in the absence of a public listing or an M&A exit, they have yet to return any cash in the form of secondary share sales back to their early-stage VC investors (that we know of). These two startups have delivered large paper returns, which, no doubt, have helped their early-stage VC backers, Point Nine, Piton Capital, and General Catalyst, to raise new VC funds.

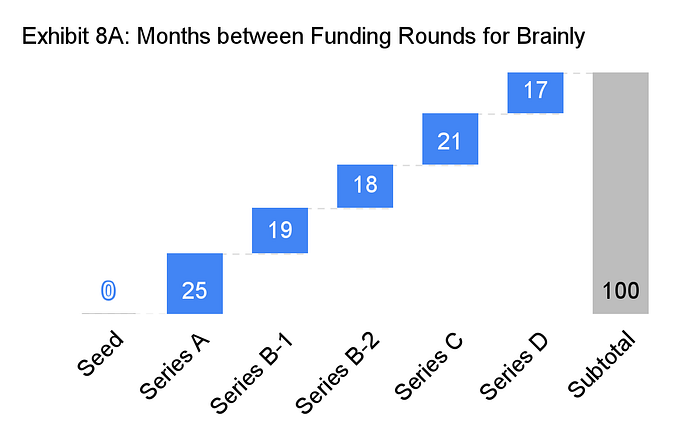

Brainly, an education technology platform, took 100 months from its initial seed round in September 2012 to raise a total of $148.5M by December 2020. This is an average of 25 months between rounds (if we consider the last date of the second series B tranche to be the end date of this round).

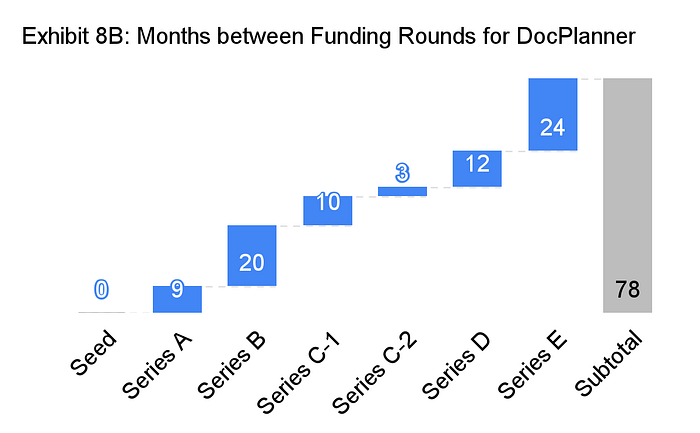

DocPlanner, a medical booking platform, took 78 months from its initial seed round in December 2012 to raise a total disclosed amount of $148M by May 2019. This is an average of 16 months between rounds (if we consider the last date of the second series C tranche to be the end date of this round). Notice that the first series C round amount was not disclosed.

The VC playbook narrative is that a startup progresses from early stage seed or series A through series B, C, D, and maybe E before going public. This can take up to ten years. Even longer these days as startups attain unicorn or decacorn status through ever larger private rounds, delaying the need to tap the public stock market for capital. Very few early-stage VC-backed firms make it to an IPO. In reality, most positive early-stage VC exits are due to M&A activities.

As our time horizon stretches back to 2006, we should expect to see a small proportion of investments publicly listed or sold by the end of 2020. In fact, out of the 259 startups in our sample, only 2 startups went public, and 6 startups were sold. Somewhat unusually, the 2 startups that went public, InteliWISE and Ten Square Games, did not raise VC capital beyond a series A stage. Equally unusual, the 6 startups which were sold did not raise VC capital beyond the seed stage.

Of these disposals, only 1 appears to have generated a significant cash-on-cash return to its investors: Codewise, which received a $1M seed investment from an angel investor in 2012 and was then sold for $36M to CentralNic Group in 2020. At a hypothetical 20% stake, assuming zero net debt, the angel investor could have made a cash-on-cash return of 7.2x or a compounded rate of return of 28% per year.

Our sample shows increased activity and amounts invested in the past 5 years in Poland. Several well-known Polish startups have reached the ultimate status of being a unicorn, with more to be expected given the level of cash being added to the system.

Our sample does not show an increase in strategic M&A whereby fast-growing global technology companies accelerate their roadmaps and talent pool through small bolt-on acquisitions of Polish startups. From our sample, it would appear that there are tens if not hundreds of Polish software startups without follow-on rounds, which could be on a drag-along M&A exit path initiated by their early-stage VC investors. After all, the most common VC exit path is via M&A.

Selling a software startup with limited revenue traction takes a lot of patience and an extensive outreach program to potential investors. An excellent external advisor can complement the support received from minority VC investors during the M&A exit process, enhance the outcome, and protect the interests of a tech entrepreneur.

Approach

We used publicly available information as a source and identified Polish seed and series A investments in software startups during the 15 years between 2006 and 2020. Then we included any other transaction done by these software startups, including follow-on rounds (Series A to E), IPOs, and M&A transactions, as well as other types of rounds, such as Accelerator, Angel, Pre-Seed, Crowd, Grant, Debt, Funding / Venture, and CVC in this period. For clarification, a startup that did a round or rounds which did not include either a seed or a series A round in these fifteen years would not be included in our sample.

In total, we found 449 different types of funding rounds done by 259 Polish software startups, supported by at least 187 different investors. Not all financing rounds disclose the amount invested or the identity of the investors. 242 rounds included both the amount raised and the identity of investors, whereas, in 89 and 93 rounds, the amount or the identity of investors were not disclosed, respectively. In 25 of the rounds, both amounts raised and the identity of investors were not disclosed.

Furthermore, even if we did our best, there’s no guarantee that we have identified all the relevant funding rounds. To easily illustrate the trends, we’ve visualized the information in three five-year periods: 2006–2010, 2011–2015, and 2016–2020.

For comparison, we converted all currencies into US dollars at a fixed exchange rate.

First published on Medium.